CALMS: A Practical Framework to Support Clients with Insomnia

- Louise Berger

- Nov 22, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Jan 27

"If sleep does not serve an absolutely vital function, then it is the biggest mistake the evolutionary process has ever made"

- Allan Rechtschaffen

Introduction

Sleep is fundamental to health. We spend around one third of our lives sleeping (or trying to). Unsurprisingly, when sleep falters, the consequences ripple across daily life; mood, relationships, concentration, productivity, health and wellbeing all decline.

Insomnia is one of the most common and often-overlooked clinical conditions. Around 10% of adults meet the criteria for insomnia disorder,1 with even higher rates among those with long-term health conditions.2

Occupational Therapists (OTs) are well-placed to support clients with insomnia. Their expertise bridges the biological, psychological and social components of sleep - from managing anxiety and supporting behaviour change, to understanding how the environment, daily routines and meaningful activities influence sleep quality.

However, many Occupational Therapists receive little formal training in sleep and their interventions are often limited to sleep hygiene advice. This article introduces the CALMS framework. A practical tool integrating evidence-based techniques, to help healthcare professionals confidently address insomnia in everyday practice.

Understanding insomnia

Insomnia is characterised by difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep or waking too early, despite adequate opportunity. While short-lived poor sleep during stressful periods is fairly common, insomnia disorder is diagnosed when these problems occur at least 3 nights per week for 3 months or longer, causing significant distress or daytime impairment.3

Insomnia is now understood as a 24-hour disorder, marked by hyperarousal both day and night. Clients often describe being "tired but wired," exhausted but unable to switch off. Unlike sleep apnoea or insufficient sleep opportunity, insomnia rarely causes persistent daytime sleepiness. If this is the main complaint, other causes should be considered.

Crucially, insomnia is not just a symptom of other conditions. Evidence shows it frequently persists unless treated directly, even if the co-morbid condition (such as pain or depression) improves.2

How insomnia develops: The 3Ps model

A helpful way to conceptualise insomnia and why it persists, is through Spielman's 3Ps model 4:

-Predisposing factors- are characteristics that increase vulnerability, such as being a worrier, a perfectionist or female sex. Alone, they do not cause insomnia, but they raise the likelihood of developing it.

-Precipitating factors- are the triggers that initiate sleep disruption, such as stressful life events or illness. For many, sleep returns to baseline quickly, but in around 10% of people the insomnia evolves into a chronic problem.

-Perpetuating factors- explain why. These are the thoughts and behaviours people adopt in response to poor sleep, which inadvertently maintain insomnia. Perpetuating factors include:

Cognitive

Catastrophic thoughts, such as "If I don’t sleep, I won't cope tomorrow"

Rigid beliefs, such as "I must get eight hours"

Attentional bias - prioritising attention towards sleep-related thoughts/cues

Sleep preoccupation - excessive rumination about sleep

→ These heighten anxiety, increase arousal and, paradoxically, reduce the chance of sleep.

Behavioural

Extending time in bed, such as early nights or lie-ins

Napping

Withdrawing from daytime activities

Lying awake in bed

Attempts to force sleep (sleep effort)

→ These behaviours weaken sleep pressure and reinforce the bed-wakefulness association.

Together, these perpetuating factors create a vicious cycle, whereby worry fuels arousal, arousal disrupts sleep, coping strategies backfire and each poor night reinforces the cycle:

The 3Ps model helps clinicians reframe insomnia as something that can change. Clients may feel their sleep is untreatable especially when associated with chronic challenges such as pain or depression. By highlighting how perpetuating cognitive and behavioural factors maintain insomnia, OTs can identify areas for improvement, even when other chronic conditions persist.

CBT for Insomnia (CBT-I)

CBT-I is the recommended first-line treatment, supported by decades of randomised control trials and meta-analyses.5

CBT-I is a non-drug, multicomponent approach which, unlike CBT for anxiety or depression, specifically targets the cognitive and behavioural factors that maintain insomnia. CBT-I integrates:

Behavioural strategies

Stimulus control

Sleep restriction

Relaxation techniques

Cognitive strategies

Psycho-education

Challenging dysfunctional beliefs

Reframing catastrophic thinking

Reducing sleep effort

While sleep hygiene forms part of psycho-education, it's rarely sufficient on its own to treat chronic insomnia - just as brushing teeth won't fix a cavity.

Importantly, although CBT-I is traditionally delivered by those with specialist training, key CBT-I principles can be safely and effectively applied by Occupational Therapists in everyday practice.

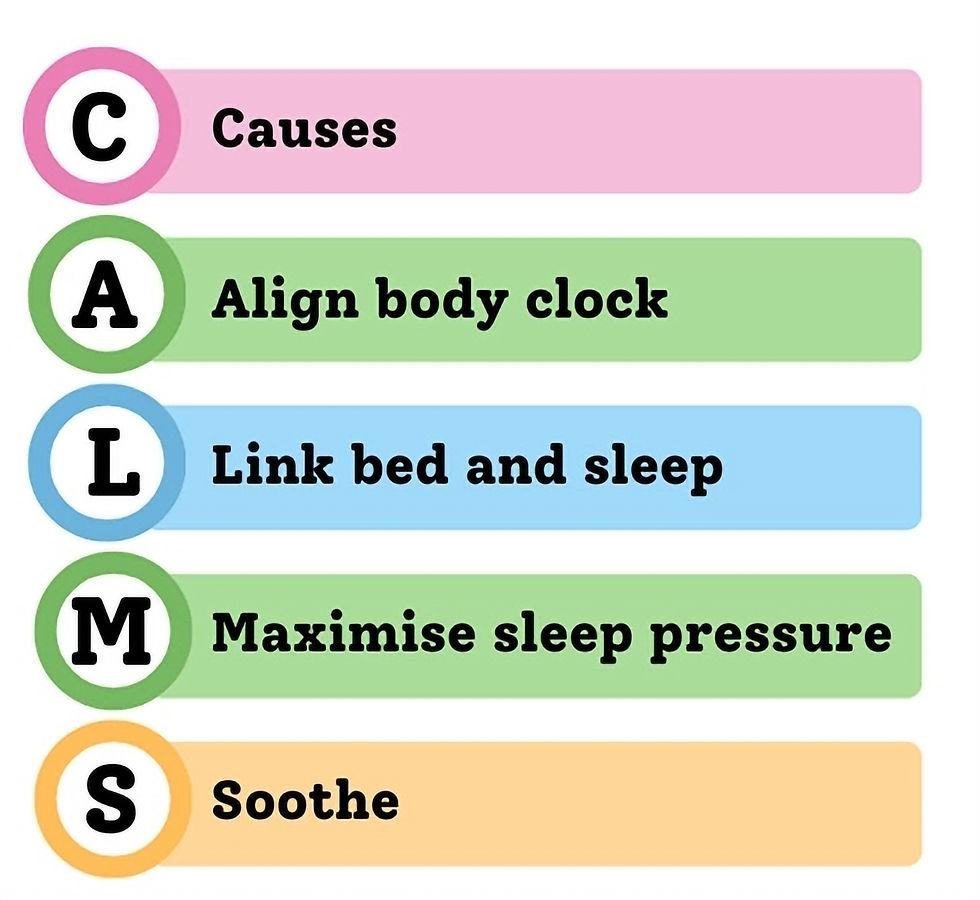

The CALMS framework

This framework translates core CBT-I principles into a practical, memorable structure for addressing insomnia:

-C - CAUSES-

Consider factors contributing to poor sleep and address any quick wins.

Causes may include:

Lifestyle factors - irregular routines, noisy sleep environment, excessive caffeine or stress

Medical factors - pain, health conditions, or medication side effects

Cognitive factors - dysfunctional sleep beliefs, catastrophic thinking and sleep effort

Key interventions:

Use sleep diaries, such as that from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, to help identify potential causes and sleep patterns.

Address obvious contributors where possible, such as stress management, environmental adjustments, reviewing medication with a GP.

Provide psycho-education on normal sleep - for example, "waking at night is normal" and "sleep need is individual" - to correct myths and reduce anxiety.

Challenge catastrophic thoughts, such as "I won't cope tomorrow", whilst developing more balanced alternatives - for example "I've always got through before, even when I haven't felt my best" - to reduce sleep anxiety.

Address sleep hygiene where relevant, framing it as supportive rather than curative.

Instil hope and reassurance that insomnia is treatable and that CBT for Insomnia goes far beyond generic sleep hygiene.

Emphasise that sleep cannot be forced; chasing it only backfires. Adopting a mindset of 'caring less' about sleep and resisting the urge to clock-watch both help reduce anxiety and sleep effort - paradoxically making sleep more likely.

[Note] Not all causes can be identified or modified, therefore over-focusing on finding 'the cause' may divert attention from targeting perpetuating factors and keep clients stuck.

-A - ALIGN body clock-

Circadian rhythms are central to sleep. Irregular wake times, poorly timed light exposure and variable meal timing can perpetuate insomnia.

Key interventions:

Set a consistent wake time, ideally that suits your client's chronotype (their natural biological tendency to feel sleepy and alert at certain times). This anchors your body clock and supports regular sleep onset at night.

Advise natural light within an hour of waking, like a short walk or coffee outside. Morning light helps shift your body clock earlier, supporting timely sleep onset.

Conversely, reduce evening light exposure in the hours before bed, using dimmer switches, lamps and reduced screen brightness.

Support consistent meal times and advise against late-night eating.

Encourage meaningful daily activities and routines, to strengthen circadian cues.

[Note] Focus on wake time as the primary anchor, rather than rigid bedtimes. Gradual changes may be needed for clients with disrupted schedules.

-L - LINK bed and sleep-

Repeatedly lying awake in bed will condition the brain to associate the bed with wakefulness. Clients might describe, "I'm nodding off on the sofa but, once in bed, it's like a light turns on."

Key interventions:

Advise only going to bed once genuinely sleepy - not just tired.

Limit bed use to sleep and intimacy, to reinforce the bed-sleep link.

If awake for 20 minutes, advise "give up and get up" - i.e. leave the bed and do something calming and enjoyable. Return to bed once sleepy.

[Note] For clients with mobility issues, recommend "give up and sit up" - i.e. engage in a calming activity while upright, rather than lying awake.

-M - MAXIMISE sleep pressure-

Sleep pressure (or sleep appetite) builds the longer we stay awake and is boosted by activity. Coping behaviours - such as naps, early bedtimes, lie-ins or avoiding exercise - reduce sleep pressure.

Key interventions:

Maintain consistent wake times - even after poor nights.

Discourage lie-ins and naps.

Encourage engagement in meaningful daytime activities and exercise, to build natural sleep pressure.

If someone spends much longer in bed than they sleep, consider reducing time in bed by ~60 minutes, via later bedtime or earlier wake time. This is to improve sleep efficiency.

[Note] CALMS does not use formal 'sleep restriction therapy', which requires specialist training. Instead, it applies a gentler approach to consolidate sleep and reduce wakefulness. Check for daytime sleepiness first, such as by using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale and monitor closely in clients with excessive daytime sleepiness.

-S - SOOTHE body and mind-

Reduce physiological and cognitive arousal in the day and at night.

Key interventions:

Teach relaxation techniques, such as progressive muscle relaxation, paced breathing or visualisation. Encourage daytime and evening practice - not as a way to force sleep, but to support winding down. Free apps, like Insight Timer, offer guided audio, which can help clients learn these techniques.

Suggest cognitive strategies - such as constructive worry or journaling - to reduce mental arousal.

Suggest paradoxical intention (keeping eyes open) to reduce sleep-related performance anxiety.

Establish a buffer zone between work/chores and bedtime, to signal winding down.

[Note] Like exercise, one session won't produce lasting change. Relaxation is a skill that improves with regular practice.

Bringing CALMS into everyday practice

By using CALMS, Occupational Therapists can move beyond generic sleep hygiene, to deliver evidence-based interventions that address the core mechanisms of insomnia.

CALMS can be incorporated into routine occupational therapy care as follows:

Assessment

Explore routines, beliefs and behaviours that perpetuate insomnia.

Examples: Irregular sleep-wake times; catastrophic thoughts about sleep; excessive time-in-bed; sleep effort.

Intervention planning

Adjust schedules and encourage strategies that support sleep.

Examples: Consistent wake times; morning light exposure; activity; relaxation strategies.

Education

Provide clear explanations about insomnia and its mechanisms.

Reduce fear and instil hope.

Examples: Normalising night waking; explaining how sleep-effort backfires.

Follow-up

Set collaborative goals and support gradual adjustments.

Build confidence in natural sleep ability.

Signpost to CBT-I with a trained provider, if needed.

Limitations and onward referral

The CALMS framework is designed for use by any healthcare professionals.

For complex cases, such as suspected sleep apnoea, parasomnias, severe psychiatric comorbidity - or when CALMS is insufficient - refer to a sleep specialist, for further investigation or CBT-I.

Conclusion

Insomnia is common, chronic and often disabling - but highly treatable. When ignored, it causes unnecessary suffering and arguably limits the therapeutic benefit of other occupational therapy interventions.

The CALMS framework provides a practical, evidence-based approach for Occupational Therapists to address insomnia - enabling them to tackle sleep directly as a vital occupation.

By embedding these strategies into everyday practice, Occupational Therapists can improve clients' sleep, wellbeing and engagement in the occupations that give life meaning.

Louise Berger leads the outpatient Insomnia Clinic within the Sleep Clinic at Royal Surrey County Hospital, one of only a few NHS insomnia clinics in the UK. This provides tailored, evidence-based care for individuals with chronic sleep difficulties (including insomnia), alongside co-morbid sleep conditions.

Beyond her clinical work, Louise is passionate about translating sleep science into practice, improving access to care and shaping how insomnia treatment is delivered - through teaching, mentoring, speaking and contributing to professional and clinical guidelines.

Louise also coaches clients in sleep globally, through BetterUp, serves as a trustee for the British Society of Pharmacy Sleep Services and co-edits the British Sleep Society newsletter.

Louise welcomes connections with those passionate about sleep on LinkedIn:

References

Morin, C.M. and Buysse, D.J. (2024) Management of insomnia. New England Journal of Medicine, 391(3), pp.247-258.

Morin, C.M. and Jarrin, D.C. (2022) Epidemiology of insomnia: prevalence, course, risk factors and public health burden. Sleep Medicine Clinics, 17(2), pp.173-191.

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Spielman, A.J., Caruso, L.S. and Glovinsky, P.B. (1987) A behavioral perspective on insomnia treatment. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 10(4), pp.541-553.

Van Straten, A., van der Zweerde, T., Kleiboer, A., Cuijpers, P., Morin, C.M. and Lancee, J. (2018) Cognitive and behavioral therapies in the treatment of insomnia: a meta-analysis. Sleep medicine reviews, 38, pp.3-16.

© 2025 Louise Berger. All rights reserved.

%20(dark%20background).png)

Comments